2023 looks to be another dynamic year in the automotive business. The quickening transition to electric vehicles (EVs), fluctuating prices and interest rates, and uncertain consumer confidence all promise to impact what happens in this industry that plays such a pivotal role in the U.S. economy.

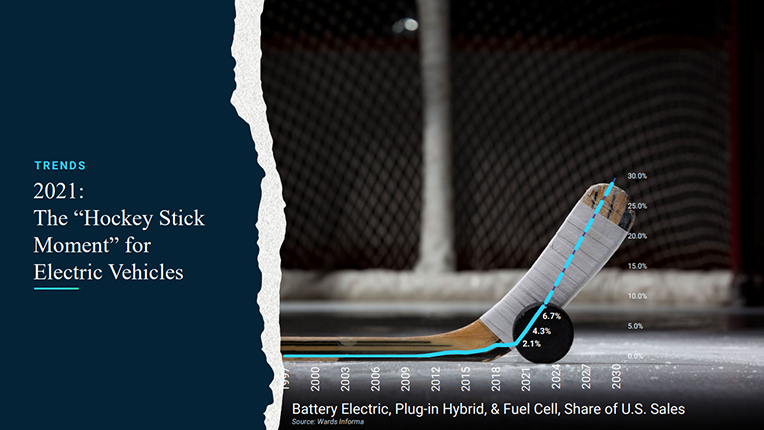

“Are we really at that hockey-stick moment that we've been talking about for decades in the EV world?” Dziczek asked, as she shared a slide that showed sales starting to move sharply upward, like the blade of a hockey stick. “I think we are.” Data show the U.S. market share of plug-in vehicles – plug-in hybrids or those powered fully by battery cells or fuel cells – jumping from under 2.1% in 2020 to 4.3% in 2021 and then to 6.7% in 2022. When you add conventional (non-plug-in) hybrid vehicles to the picture, the climb was from over 5% market share in 2020 to more than 12% in 2022.

And the number of options is growing as well. North American plants made 20 plug-in vehicles in 2020. There will be ten times that number by 2030, according to some estimates.

Affordability is one of the biggest issues hanging over the electric vehicle transition. “Safe, reliable transportation matters,” Dziczek said, citing the early days of Ford, when the workers who built Model Ts could also afford to buy them.

But EVs remain pricey, often too pricey for consumers who would otherwise like to experience their many advantages. Battery electric vehicles cost about one third more than other vehicles, and current EV ownership is concentrated in high-income households on the coasts and in the mountain states.

Despite the pandemic and its disruptions, the manufacturers have been making money and lots of it. And this summer and fall they’ll be negotiating expiring contracts with the major unions. “Very profitable companies will have a difficult time telling the union that they can’t give them what they want,” said Dziczek. At the same time, the unions will be seeking to guarantee security for workers as manufacturing – the very way in which vehicles are made – undergoes a seismic shift.

The estimated cost of raw materials per average vehicle was about $2,000 in 2016. Since then, it’s climbed to over $3,000 in 2018, plunged almost all the way back to $2,000 in 2020, and then shot up to some $6,000 in 2022. Thankfully for the question of cars becoming more affordable, there’s been a significant decrease in materials prices in the past couple of months.

This rich mix, coupled with low production volumes in recent years, could keep supply tight and the price of used vehicles elevated in coming years, with comparatively fewer vehicles of moderate price entering the market. There still seems to be considerable pent-up demand in the new vehicle market, but it’s unclear if consumers will continue to prefer luxury models and features or if the mix will become less rich as supply constraints ease and production recovers.

Much of that rise came in 2021, when the average transaction price for light vehicles (passenger cars, crossovers and SUVs, plus pickups and vans) climbed more than 19% in six months. Those costs appear to have hit a plateau in recent months. But what has been climbing is the interest consumers pay: Average finance rates for light vehicles hit about 6.5% in the fourth quarter of 2022, a 1.5% climb during the year. Yet sales were slightly higher in the fourth quarter than in the first.

And the consensus among forecasters is that manufacturers will sell more cars in 2023 than they did in 2022, although still significantly fewer than they did in 2019.

The price of an EV is determined by a complex mix of factors. But manufacturers seem a long way from reaching a perceived market sweet spot of offering a $30,000 vehicle that has 300 miles of battery driving range.

Still, Dziczek said, current purchase and manufacturing incentives, both state and federal, are pushing EVs toward becoming more affordable. Introduction of new models and recovery in the production supply chain and moderating costs of raw materials should help, too.